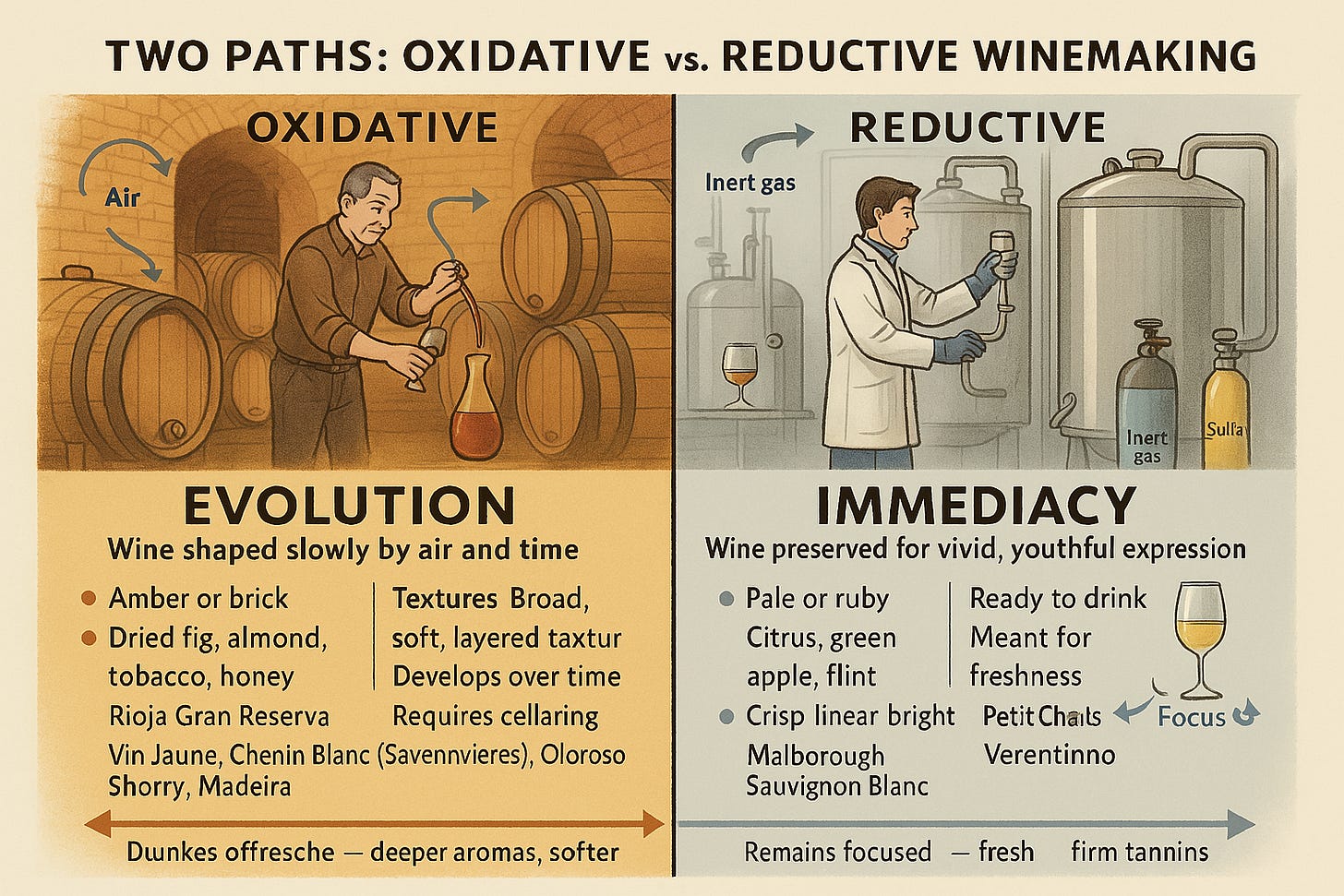

36. Oxidative vs. Reductive Winemaking: How Oxygen Shapes a Wine’s Style, Aging, and Expression

In winemaking, the distinction between oxidative and reductive approaches isn’t just about technique—it’s a matter of philosophy. It’s how a winemaker thinks about time. About how a wine should grow. About whether it should open gradually or speak right away. The terms themselves—oxidative and reductive—can sound clinical. But what they really point to are two different relationships with air, and through that, two different ways of imagining what a wine is meant to become.

A wine made oxidatively is shaped by the presence of oxygen over time. That oxygen may enter during fermentation, during aging, or both. It may come from open-top vats, from neutral oak barrels, from racking, or from deliberate exposure. But what matters isn’t simply that oxygen is there—it’s that its presence is invited. The wine is allowed to evolve. It loses the tight grip of youth and gains something more settled: not just fruit, but texture; not just aroma, but resonance. This is what we mean by evolution. A wine like traditional Rioja—aged in American oak for years before release—tells a story that’s layered, developed, reflective. The fruit softens into cherry tobacco, dried fig, cedar. The wine speaks slowly and with detail, as if it’s been waiting to be asked.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mitchell’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.